Harmonic series (mathematics)

In mathematics, the harmonic series is the divergent infinite series:

Divergent means that as you add more terms the sum never stops getting bigger. It does not go towards a single finite value.

Infinite means that you can always add another term. There is no final term to the series.

Its name comes from the idea of harmonics in music: the wavelengths of the overtones of a vibrating string are , , , etc., of the string's fundamental wavelength. Apart from the first term, every term of the series is the harmonic mean of the terms either side of it. The phrase harmonic mean also comes from music.

History

The fact that the harmonic series diverges was first proven in the 14th century by Nicole Oresme,[1] but was forgotten. Proofs were given in the 17th century by Pietro Mengoli,[2] Johann Bernoulli,[3] and Jacob Bernoulli.[4][5]

Harmonic sequences have been used by architects. In the Baroque period architects used them in the proportions of floor plans, elevations, and in the relationships between architectural details of churches and palaces.[6]

Divergence

There are several well-known proofs of the divergence of the harmonic series. A few of them are given below.

Comparison test

One way to prove divergence is to compare the harmonic series with another divergent series, where each denominator is replaced with the next-largest power of two:

Each term of the harmonic series is greater than or equal to the corresponding term of the second series, and therefore the sum of the harmonic series must be greater than or equal to the sum of the second series. However, the sum of the second series is infinite:

It follows (by the comparison test) that the sum of the harmonic series must be infinite as well. More precisely, the comparison above proves that

This proof, proposed by Nicole Oresme in around 1350, is considered to be a high point of medieval mathematics. It is still a standard proof taught in mathematics classes today.

Integral test

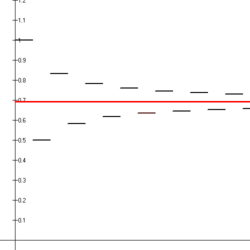

It is possible to prove that the harmonic series diverges by comparing its sum with an improper integral. Consider the arrangement of rectangles shown in the figure to the right. Each rectangle is 1 unit wide and units high, so the total area of the infinite number of rectangles is the sum of the harmonic series:

The total area under the curve from 1 to infinity is given by a divergent improper integral:

Since this area is entirely contained within the rectangles, the total area of the rectangles must be infinite as well. This proves that

The generalization of this argument is known as the integral test.

Rate of divergence

The harmonic series diverges very slowly. For example, the sum of the first 1043 terms is less than 100.[7] This is because the partial sums of the series have logarithmic growth. In particular,

where is the Euler–Mascheroni constant and which approaches 0 as goes to infinity. Leonhard Euler proved both this and also that the sum which includes only the sum of the reciprocals of the primes diverges also diverges, that is:

Partial sums

The finite partial sums of the diverging harmonic series,

are called harmonic numbers.

The difference between and converges to the Euler–Mascheroni constant. The difference between any two harmonic numbers is never an integer. No harmonic numbers are integers, except for .[8]Template:Rp[9]Template:Rp

Related series

Alternating harmonic series

The series

is known as the alternating harmonic series. This series converges by the alternating series test. In particular, the sum is equal to the natural logarithm of 2:

The alternating harmonic series, while conditionally convergent, is not absolutely convergent: if the terms in the series are systematically rearranged, in general the sum becomes different and, dependent on the rearrangement, possibly even infinite.

The alternating harmonic series formula is a special case of the Mercator series, the Taylor series for the natural logarithm.

A related series can be derived from the Taylor series for the arctangent:

This is known as the Leibniz series.

General harmonic series

The general harmonic series is of the form

where and are real numbers, and is not zero or a negative integer.

By the limit comparison test with the harmonic series, all general harmonic series also diverge.

p-series

A generalization of the harmonic series is the -series (or hyperharmonic series), defined as

for any real number . When , the -series is the harmonic series, which diverges. Either the integral test or the Cauchy condensation test shows that the -series converges for all (in which case it is called the over-harmonic series) and diverges for all . If then the sum of the -series is , i.e., the Riemann zeta function evaluated at .

The problem of finding the sum for is called the Basel problem; Leonhard Euler showed it is . The value of the sum for is called Apéry's constant, since Roger Apéry proved that it is an irrational number.

ln-series

Related to the -series is the ln-series, defined as

for any positive real number . This can be shown by the integral test to diverge for but converge for all .

φ-series

For any convex, real-valued function such that

the series

is convergent.Template:Citation needed

Random harmonic series

The random harmonic series

where the are independent, identically distributed random variables taking the values +1 and −1 with equal probability , is a well-known example in probability theory for a series of random variables that converges with probability 1. The fact of this convergence is an easy consequence of either the Kolmogorov three-series theorem or of the closely related Kolmogorov maximal inequality. Byron Schmuland of the University of Alberta further examined[10] the properties of the random harmonic series, and showed that the convergent series is a random variable with some interesting properties. In particular, the probability density function of this random variable evaluated at +2 or at −2 takes on the value Template:Val..., differing from by less than 10−42. Schmuland's paper explains why this probability is so close to, but not exactly, . The exact value of this probability is given by the infinite cosine product integral [11] divided by Template:Pi.

Depleted harmonic series

Template:Main The depleted harmonic series where all of the terms in which the digit 9 appears anywhere in the denominator are removed can be shown to converge and its value is less than 80.[12] In fact, when all the terms containing any particular string of digits (in any base) are removed the series converges.

Applications

The harmonic series can be counterintuitive. This is because it is a divergent series even though the terms of the series get smaller and go towards zero. The divergence of the harmonic series is the source of some paradoxes.

- The "worm on the rubber band".[13] Suppose that a worm crawls along an infinitely-elastic one-meter rubber band at the same time as the rubber band is uniformly stretched. If the worm travels 1 centimeter per minute and the band stretches 1 meter per minute, will the worm ever reach the end of the rubber band? The answer, counterintuitively, is "yes", for after minutes, the ratio of the distance travelled by the worm to the total length of the rubber band is

Because the series gets arbitrarily large as becomes larger, eventually this ratio must exceed 1, which implies that the worm reaches the end of the rubber band. However, the value of at which this occurs must be extremely large: approximately , a number exceeding 1043 minutes (1037 years). Although the harmonic series does diverge, it does so very slowly.

- The Jeep problem asks how much total fuel is required for a car with a limited fuel-carrying capacity to cross a desert leaving fuel drops along the route. The distance the car can go with a given amount of fuel is related to the partial sums of the harmonic series, which grow logarithmically. And so the fuel required increases exponentially with the desired distance.

- The block-stacking problem: given a collection of identical dominoes, it is possible to stack them at the edge of a table so that they hang over the edge of the table without falling. The counterintuitive result is that they can be stacked in a way that makes the overhang as large as you want. That is, provided there are enough dominoes.[13][14]

- A swimmer that goes faster each time they touch the wall of the pool. The swimmer starts crossing a 10-meter pool at a speed of 2 m/s, and with every crossing, another 2 m/s is added to the speed. In theory, the swimmer's speed is unlimited, but the number of pool crosses needed to get to that speed becomes very large; for instance, to get to the speed of light (ignoring special relativity), the swimmer needs to cross the pool 150 million times. Contrary to this large number, the time needed to reach a given speed depends on the sum of the series at any given number of pool crosses:

Calculating the sum shows that the time required to get to the speed of light is only 97 seconds.

Related pages

References

Other websites

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite book

Mengoli's proof is by contradiction:- Let denote the sum of the series. Group the terms of the series in triplets: Since for , , then , which is false for any finite . Therefore, the series diverges.

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite book

From p. 250, prop. 16:- "XVI. Summa serei infinita harmonicè progressionalium, [et]c. est infinita. Id primus deprehendit Frater:…"

- [XVI. The sum of an infinite series of harmonic progression, , is infinite. My brother first discovered this:…]

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite OEIS

- ↑ Julian Havil, Gamma: Exploring Euler’s Constant, Princeton University Press, 2009.

- ↑ Thomas J. Osler, “Partial sums of series that cannot be an integer”, The Mathematical Gazette 96, November 2012, 515–519. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24496876?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:MathWorld

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Template:Citation

- ↑ Template:Cite journal